I love Monopoly. This puts me in the vast minority of people in every gaming group I’ve been in since I was thirteen. And while I do enjoy the game, and defend it at every turn, I do also understand that it’s a pretty shite game. I have a great deal to say about Monopoly, both good and bad.

I mean really, are we seriously f***ing doing this?!

So. Um. Hi.

It’s been just shy of four years. If you know me you’re expecting a long-winded thing here, a welcome back, apologies, new awakening screed. But no. I can’t/won’t commit to that. It’s okay, none us should feel bad. I just saw a thing that fascinated me, and it was too long a for a Facebook post. So it goes here.

Ginger Snaps

We’re watching Riverdale in our house. Teen drama with some murder mystery, all set in a re-imagining of the world of Archie Andrews, Betty Cooper, Veronica Lodge, and Jughead Jones. My wife thoroughly enjoys it. I think it’s alright. This is not a breakdown of that show, per se. But the preview for the next episode caught my eye. The gang is going away to a cabin in the woods, probably to have network-television-appropriate cuddles and maybe air out some grievances, like how egregiously out of place Archie’s music dreams are.

And they’re also going to play Monopoly. So here I am. Hi.

Americana

I feel that it’s worth it to talk a bit about the history of Archie comics. Not being an expert, we’ll just go to Wikipedia and get some background.

Archibald “Archie” Andrews started in Pep Comics #22, in December 1941. The characters’ popularity quickly led to Archie becoming a standalone series in 1942 and running until June 2015, where it gave way to a modern reinvention as part of the “New Riverdale” relaunch in July. The television series, featuring some heavy story elements (murder, organized crime, social inequality to name a few) is based off this new take.

To wit: Archie has been part of American culture since World War II, and is undergoing a renaissance of modern storytelling. Monopoly has it’s own heritage in American history, dating back to pre-depression, and is also in the throes of a cultural reinvention, though would have to argue not as successfully received. Still, to see the game being played in an episode speaks more to me than the simple foil of four bored teenagers on vacation playing the stereotypical “only board game in the house” (though that is definitely a valid interpretation); to me it is the fusion of stalwart pop-culture icons engaging in an ingrained cultural touchstone. It’s an Americana ouroboros. So it’s a shame the SouthSide snake is getting his ass kicked.

1000 Words

Before we go further, let’s get a look at the still that got us here.

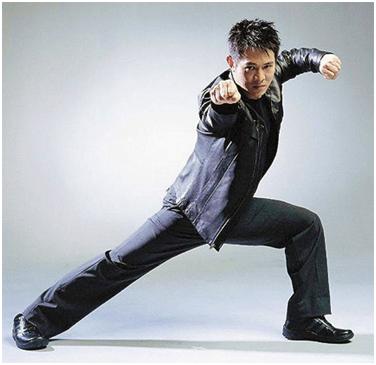

WE ARE HAVING FUN

I love this tableau. It’s the sort of thing you can either write off as scene filler, or you can get deep into the decisions made to set this scene. Which I’m gonna do.

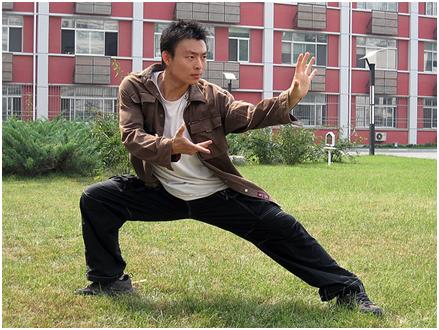

For those not watching the show: Jughead (top) is dating Betty (left), and Archie (bottom) is doing an on-again-off-again thing with Veronica (right). Jughead is a poor kid from a broken home on the outskirts of Riverdale, with a sort of ancestral rite of leadership to the show’s gang element, the SouthSide Snakes. Betty’s a sort of girl-next-door type with a damaged family and a possible un-diagnosed mental instability. Veronica is the bad girl from the big town, and the heiress to her family’s wealth, legacy, and the seedy underpinnings therein. Archie, despite the mature update of his world, remains the good-intentioned everyman from modest upbringings striving to do right and find himself in the process.

There are deliberate stylistic choices made here, even before we consider the game. Betty and Jughead are sitting on one side of the table, almost linked by the single bear-skin rug they’re standing on. Also, almost everyone is standing, which baffles me. It’s like everyone needed to be uncomfortable, except for the person winning (more on that later). The lighting has the Jughead-Betty couple in softer bluish light, and the Archie-Veronica pair in warmer light and sharper focus, made more stark by their wardrobe choices. I think this is meant to portray some sense of trustworthiness – Jughead and Betty have been constantly fighting to do what’s right, and Archie and Veronica have been swimming in murkier waters – Veronica’s joining the family business of probably f***ing people over, and Archie is I guess an FBI informant? (UPDATE: That FBI agent was a plant to test Archie’s loyalty to the Lodge family) Everyone’s drinking something dark out of tumblers. I’m guessing it’s a dark liquor like whatever scotch was handy, which is what you do when you’re 4 teenagers who found/snuck a bottle of hooch in an old cabin. The copy of Monopoly they’re playing is pretty old; the box in the upper left is the version used in 1962. It’s the sort of copy you’d see in a vacation home you’re renting; not old enough to be historic, too old to be a deliberate consideration by homeowner/renters.

You can tell a lot by the game state in this picture (photo quality aside), as well as the temperament of the players. Jughead is a free-thinking scrappy bad-boy wannabe; his deeds and money – such as they are – are scattered but still grouped and identifiable. Betty is a meticulous, high strung person; her money and deeds are all lined up, evenly spaced, drinks away from the cash and valuable deeds. Archie’s setup is fairly straightforward; deeds in groups but slightly askew, same with cash. It’s a standard, almost comforting setup, to go with the standard, almost comforting man.

Veronica’s setup I like the most; money in discrete piles, all set at the exact same angle to the board, no $1 bills because she doesn’t have time for chump change. Her monopolies are grouped by sheer power of rent potential, and organized as such (Blues are crisp, Oranges lined up but just shy of perfect, light-blues bundled). Her non-grouped properties are few, and almost disdainfully cast aside. She has no need for them, her power is absolute and her need for trading is nil.

Rich Get Richer,Blah Blah Blah-er.

Now’s a good time to talk about relative wealth. The game state is meant to be an allegory for the characters playing the game. I could have started and ended the post with that sentence and been done, but we all know that’s not my style. Let’s go from bottom to top, as I see it.

Jughead is poor; single dad in jail, semi-homeless, no financial acumen. His game state is unarguably the worst; low on cash (approx. $100 give or take), Purple monopoly with a scant 1 house on each, 2 railroads and what looks like one Red. The weakest monopoly with the weakest development and some scraps of resource. Down but not out, still fightin’, etc.

Archie’s dad is a blue-collar working-class stiff who owns his own construction business but has fallen on hard times. He’s working on a football scholarship, following a dream of music I’d like to ignore, and a good heart beset by hard times that force him to choose between his drive to do what’s right and what’s necessary. Game analog: he owns a struggling business – green Monopoly with minor development (one house, maybe two, but not three). His other deeds represent failed side ventures; one railroad, two Reds, one Magenta. He has options, he can try to use what he’s built to win, but it’s a longshot – Greens are notorious for under-performing due to their position on the other side of the Direct-to-Jail corner). His best chance for victory is shrewd trades and a quick kill. Of note: Jughead has the deed he needs to complete his Red set.

Betty’s from an upper middle class family, well off but not major players in Riverdale. She has the yellows with good development (3 houses?), and I would argue the second-best position, especially if she can complete that Magenta set (though how she does that I have no idea). What would be more interesting is if she had the color group Jughead has the final deed for; his being out but having something valuable to her would reflect their strained relationship. But that would require a different break of the Reds/Magentas so Betty and Archie shared them. Why? Well let’s go to my new favorite person…

Veronica is the daughter heiress of the richest and most suspect family in Riverdale (except the Blossoms, and I so wish Cheryl was playing in this game). And her board state is dominating. Blues with Hotels, the quintessential symbol of wealth and power in Monopoly, and also the Light-Blues with Hotels, and Oranges with major development. She owns the top, the mid, and the low-end, and has nothing really worth trading to anyone, so she stands alone.

These are all deliberate decisions made by the scene organizers to tell a story. Veronica owns powerful monopolies, a utility and railroad to represent that she has her hands in all things (and form a tenuous bond with her bf Archie via railroad), and no other color deeds that she could trade or want to. She is deliberately isolated by her holdings. Archie’s best way to win is to “kill” Jughead, take the railroads (which would give him 3) and the single deed that completes his second monopoly. Betty has a good chance but her odds are rough against her rival. She doesn’t want to rely on others, and her relationship with Archie is strained from the love triangle, but he has the one deed she needs to complete another Monopoly and shore up her position. Her bf Jughead cannot help her; he can’t really help anyone, even himself, but he has just enough to be a short-term nuisance and a long-term Hail Mary if he gets a ton of lucky rolls and a handout from the quintessential nice-guy trying to do right.

Endgame

I hope more than anything that we see the rest of the game play out. I want to see the show writers hit us hard with ham-fisted metaphors using Monopoly as their lexicon. Maybe Betty, Archie, and Jughead make some insane 3-way trade to try to fight off Veronica’s Empire. Archie could just hand Jughead a monopoly because he feels some need to help his downtrodden poor friend, and Jughead’s pride won’t allow it and he tries to flip the table but he can’t because it’s a heavy-ass tree trunk slice and he can’t even ruin the game properly. I want Veronica to start taking players out, claiming their tokens in her manicured hand, saying something like “it’s okay boys, it’s only a game. Right?” And gives a knowing smirk and a wink toward her boy-toy Archie while Betty watches, silently fuming.

Also, it infuriates me that they have so much money in the system but aren’t developing their monopolies. What the hell are you waiting for? You got the rest of the game right, do you just not remember how mortgaging and 3-house rent breaks work? Veronica gets it, her monopolies are developed for maximum effectiveness. God I hope she crushes you all.

To Be Continued

Now, it’s late where I live. It’s almost 2 AM and I’m close but not done with all I want to put in this post. I want to talk about why there’s so much money left on the board; Jughead’s poverty aside, the other players have so much money for this late in the game. I’m pretty sure it’s because they use the Free Parking rule, as evidenced by the money in the center of the table in a shape that suggests it’s not rent being exchanged. I want to talk more about each player’s chances to victory, and the path they must take. And I really want some sort of photo-editing capability that can answer the niggling question of who has the Reds and the Magentas – I wrote under the idea that Archie has two Reds and one Magenta, Betty has two Magentas, and Jughead has that final Red. This matters to me, and I think both states would say something different about their relationships.

I also wanted to finish this post in an hour and throw it out there. No biggie. No need for links, photos, screenshots. But we know that isn’t my style.

I may come back to this post tomorrow. Or when the episode airs.

So. Bye for now.